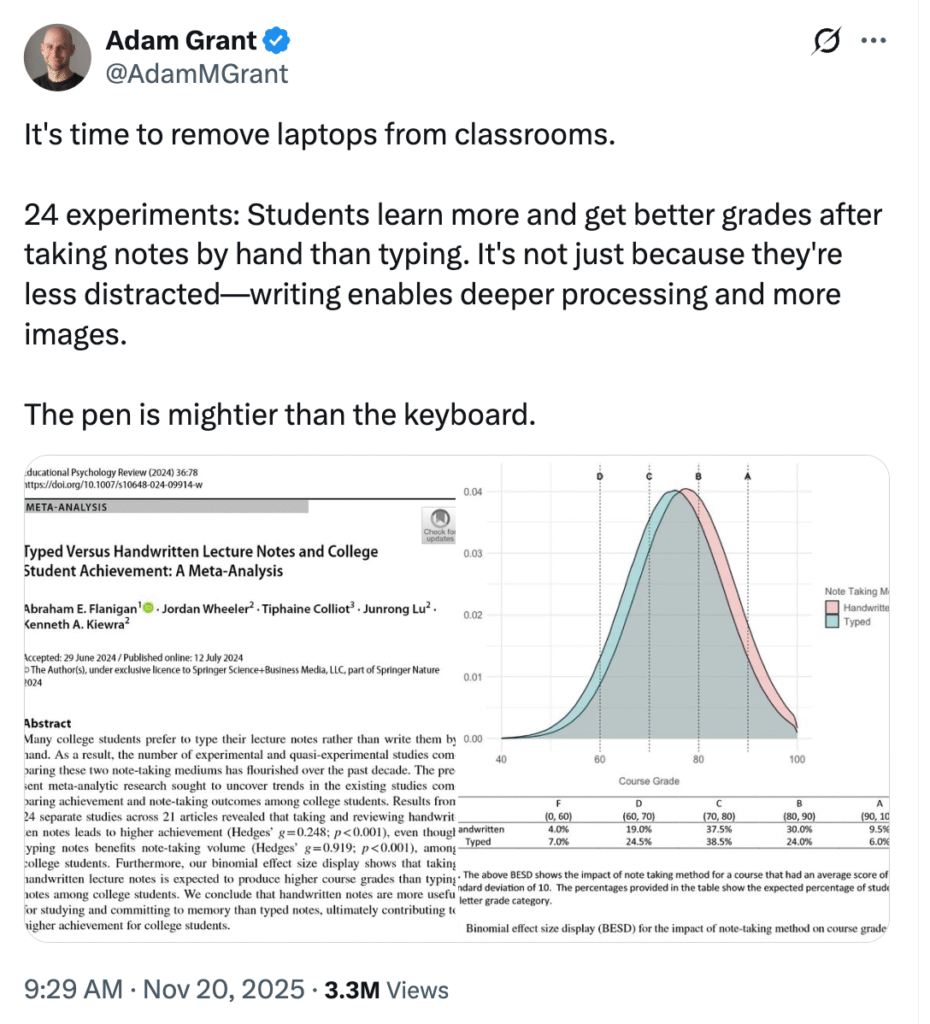

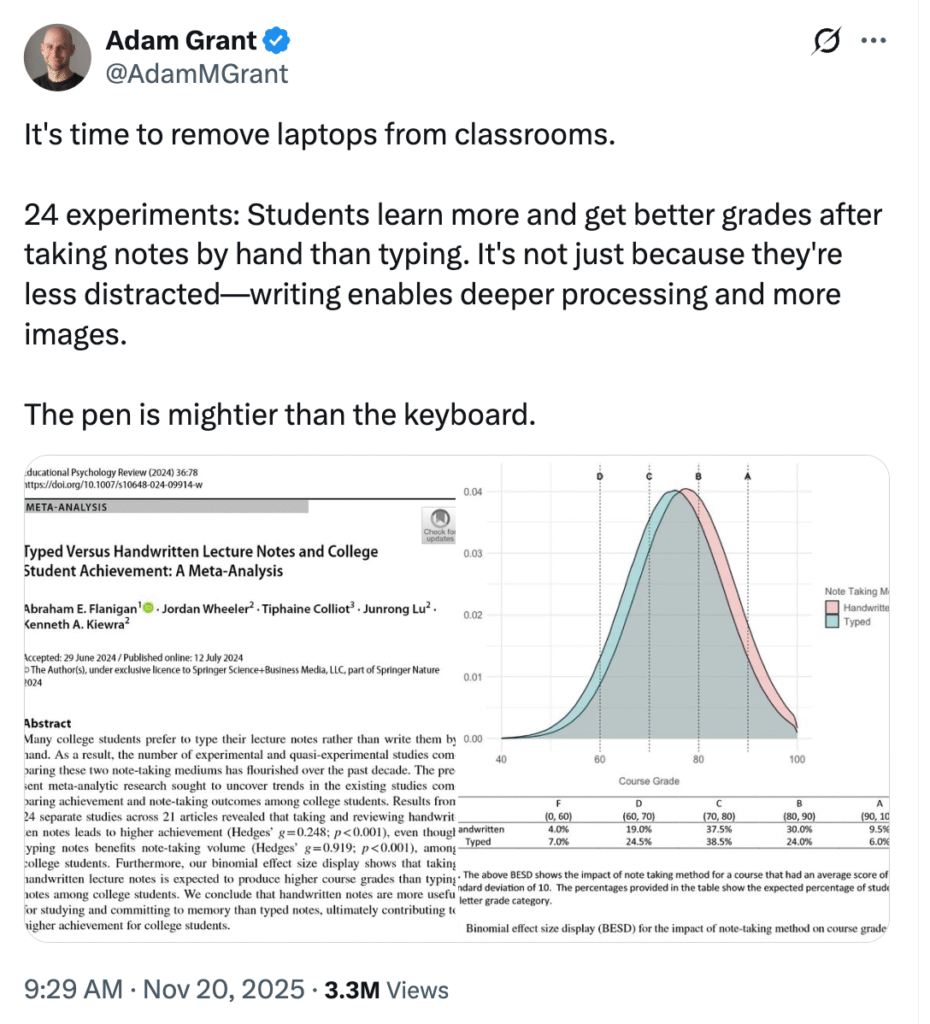

This is also happening when many are advocating that technology should no longer be in classrooms, as evidenced not only by this Adam Grant tweet but the responses as well:

As much as I see new opportunities that technology provides for learning, it is our thinking about how we leverage technology more (if not 100%) than any technology itself. In fact, the technology has become so “intelligent” that if we are not intentional in how we use it, it can definitely dumb us down. I wrote about this in my latest book, “Forward, Together“:

To be honest, I have my own reservations about new technologies, and there have been many conversations on why you should or shouldn’t utilize AI in current classrooms. As the technology gets better, if we aren’t intentional in how we use it, it’s easy to become dumber in the process.

Strangely enough, my apprehension is part of the reason why I think schools should learn and teach new technologies—so we can guide students from a place of wisdom and experience, instead of playing the game of Lord of the Flies and throwing a bunch of kids on Technology Island to fend for themselves, hoping Piggy won’t die (spoiler alert: Piggy dies).

And as much as I know, we can be part of the solution, we can also become part of the problem. Our inclination to gravitate toward the “new shiny thing” is not only with technology in education, but with ideas and initiatives in general.

Here is an example.

I was speaking at a conference in a state that I had never been to before, and a district administrator who had seen me speak in another state was there. He asked me, “Are you going to be sharing what you did when I saw you last year?” I told him that although I continually evolve the ideas and examples I share, much of what I was going to share would have been similar to what he had seen before. But since about 98% of the audience had never seen me speak before, it didn’t make sense to give an entirely new presentation to the 2% who had heard the ideas before. He said he was disappointed that it wouldn’t be new stuff, so I stopped him and asked, “What did you do with the old stuff?” Was there any differentiation in his own practice from when he saw me speak? He had no response, which told me the answer, and I said that perhaps a refresher isn’t the worst thing.

It is easy to want more and more and more, but that doesn’t promote depth in learning.

And I can’t say I have been immune to that line of thinking.

In “The Innovator’s Mindset” (2015), I shared how I started my principalship by overwhelming staff with the “latest and greatest” tools:

During my first year as a principal, I was pretty excited about all of the opportunities that technology provided my staff. I saw all the awesome websites and tools that were out there and thought we would be crazy not to take full advantage of all of that free stuff. I passed on to my staff anything that I could get my hands on. Twitter supplied countless links with articles about how to make education better, as well as tips and techniques that could be implemented in the classroom right away. I felt it was imperative to share the tips and tweets with my staff; I wanted to light a fire under my team so we could use all those resources and ideas.

Bad move.

The more I shared, the more I noticed how overwhelmed my staff seemed. The more choices I provided them, the less they did with each one. It was too much. I also noticed that the staff members who did embrace everything I shared were only scratching the surface of how these tools and ideas could impact the learning experiences for their students. Our school started to seem “garden variety.” The practice had made us knowledgeable in all but masters of none. This was no one’s fault but my own. I had simply given my team way too many options without a clear focus.

As I continue to share in the book, I learned from that mistake. So in my second year, we decided to leverage three tools for the next three years to focus on doing more with less (this is literally from the chapter titled “Less is More“, which was a significant focus of the book).

And one of those initiatives was digital portfolios, which I still advocate for to this day (more on that in a second).

But why did I focus on sharing so many tools at first? Because I copied what I saw at conferences at the time, and it is still happening. The “50 Best Websites” for learning in an hour sessions have now been replaced with similar “50 AI Tools” keynotes at conferences. And why do conferences provide those sessions? Because they fill a room. Every. Time.

We say we want depth, but are easily drawn to “new and shiny.”

The focus should never have been on the technology, but on the learning, which is why, for example, I have advocated for digital portfolios for as long as I can remember. And not just “digital portfolios” but blogs as portfolios (blogfolios was a term once used, but I just can’t!).

It was the learning that I was drawn to, not the tech.

And how did I learn about it?

Because I went first.

This post you are currently reading is on my “blog/portfolio” that I started as a principal, not because I wanted to get my thoughts out to the world, but we were considering digital portfolios for our students, and it didn’t make much sense to try to teach something we had never learned ourselves. So I went first. And at the time, we had considered websites like Google Sites or Weebly (is that a thing still?), but my concern was that they would become digital dumping grounds. Kids would take a picture or post a link to something, and move on. The “blogging” was what I was drawn to because it promoted traditional literacy, but it could be accelerated.

For example, if you had a journal in a class, and you wrote in a notebook as a student, and you had 30 students, and you wrote a comment to each student, who is becoming the most literate in the process? The teacher has a 30:1 writing ratio.

But if you had students write in a blog and then have them comment on five other students’ blogs, the writing would increase, and you might also get excited about receiving a comment and respond to it. More writing for the student is better, and this process could improve the ratio in the student’s direction. Of course, you can do variations of this in a notebook, but not to the same extent. The focus wasn’t on the “blog” as much as it was about the opportunity to write more.

When I started this process, I had no idea what it would lead to for me personally. Two thousand posts and six books later, I realize it has not only pushed my learning but also opened doors I didn’t even know existed. My goal is to be intentional about how I help students and schools see the same opportunities I have benefited from.

I reflect on all of this after a conversation on my podcast with Karen Vaites, a huge literacy advocate who has written extensively about it on her Substack. , who almost seemed surprised that I advocated for the importance of literacy and numeracy as the foundations we build upon, while still advocating for aspirational opportunities for our students.

I started thinking about Karen’s surprise and questioned myself. Was this focus on “literacy and numeracy” new for me? Self-doubt began to creep in.

Luckily, I have been creating content forever. So I searched my Google Drive for the write-up regarding the Digital Portfolio initiative I did in my last school district and found this:

I created this so long ago that I called it an “Electronic Portfolio” because I guess that was cool in 2011.

So I opened the document, and what was listed as the initiative’s top priority?

And that is something I have continuously advocated for.

In 2014, I wrote “5 Reasons Your Portfolio Should Be a Blog,” and shared the following:

2. An opportunity to focus on “traditional” literacy.

Many people prefer portfolios to have links to examples of work which is great for the “showcase” aspect. What I like about a blog is the opportunity to write, which is obviously a huge part in the work that we do in schools. There is a difference between having great ideas and the ability to communicate great ideas. In our world, we need the ability to do both. The other aspect of this is that when many outsiders see that students are doing more work in a “digital format”, they may have questions around the idea that we do not do “the basics”. With a blog, we are not only focusing on the “basics”, but we are actually doing them better. The more we write, the better we become at writing. That being said, I love a quote I heard from Dr. Yong Zhao saying that “reading and writing should be the floor, not the ceiling.” It is crucial, but there is so much more we can do with a blogging format.

With all of this, let’s go back to the Adam Grant tweet:

As I shared in last week’s post, we have to distinguish between “learning” and “retention.” Retention is crucial to learning, but it is not learning itself. In a world with all of the information in the world, what we do with information matters more than ever.

If people believed that “technology” was the cure to the issues with education, they were wrong. That was never my belief. How we think, and ultimately the actions that followed those thoughts, with or without technology, was and is the only thing that will ever make a better school experience for both kids and adults.

Many advocates against technology in schools benefit from using the very tools they say kids shouldn’t have access to. I have benefited tremendously, in many ways, and my goal is to share those strategies with others. The technology might have opened a new door, but I had to figure out how to go through it.

When we look at many of the problems we see with technology, social media, phones, etc., were they caused because we overtaught these things, or because we undertaught them, threw them into the classroom, and hoped for the best? We should never teach these things because “they are here anyway,” but because they can provide opportunities that did not exist previously. But that will never just be technology; it is our thinking and creating that ultimately deepen our learning.

Focusing on “depth” rather than “new” is always the best strategy forward.

Technology accelerates everything, good and bad. The focus should be on accelerating the good.

As I said in 2015, and still believe today, “Less is more.”