Should schools always listen to student voice?

Yes.

Do they have to always act upon what they hear from their students?

Kind of.

Here is what I mean by that.

As adults, we have certain experiences, expertise, and wisdom in various situations. Although it is important to hear students’ voices, it is not always feasible to implement their suggestions, or even in the best interest of the student, to act upon what is heard from them.

Here is an example.

As a grade 12 student in Canada, I ran for class president on the platform of extending lunch from one to two hours, not because it was in the best interest of learning, but because I, like many of my fellow classmates, wanted to be in class way less rather than more. Although I won the election, I was never able to implement the promises made in my campaign, which gave me valuable early experience of a successful politician!

So why the “kind of” response?

Because if you are going to listen to your students and can’t implement their suggestions in any way, I think it’s a great conversation to explain why. They not only learn from the process, but I also think it validates the idea that we seek the feedback of those we serve, and we can’t always act upon it.

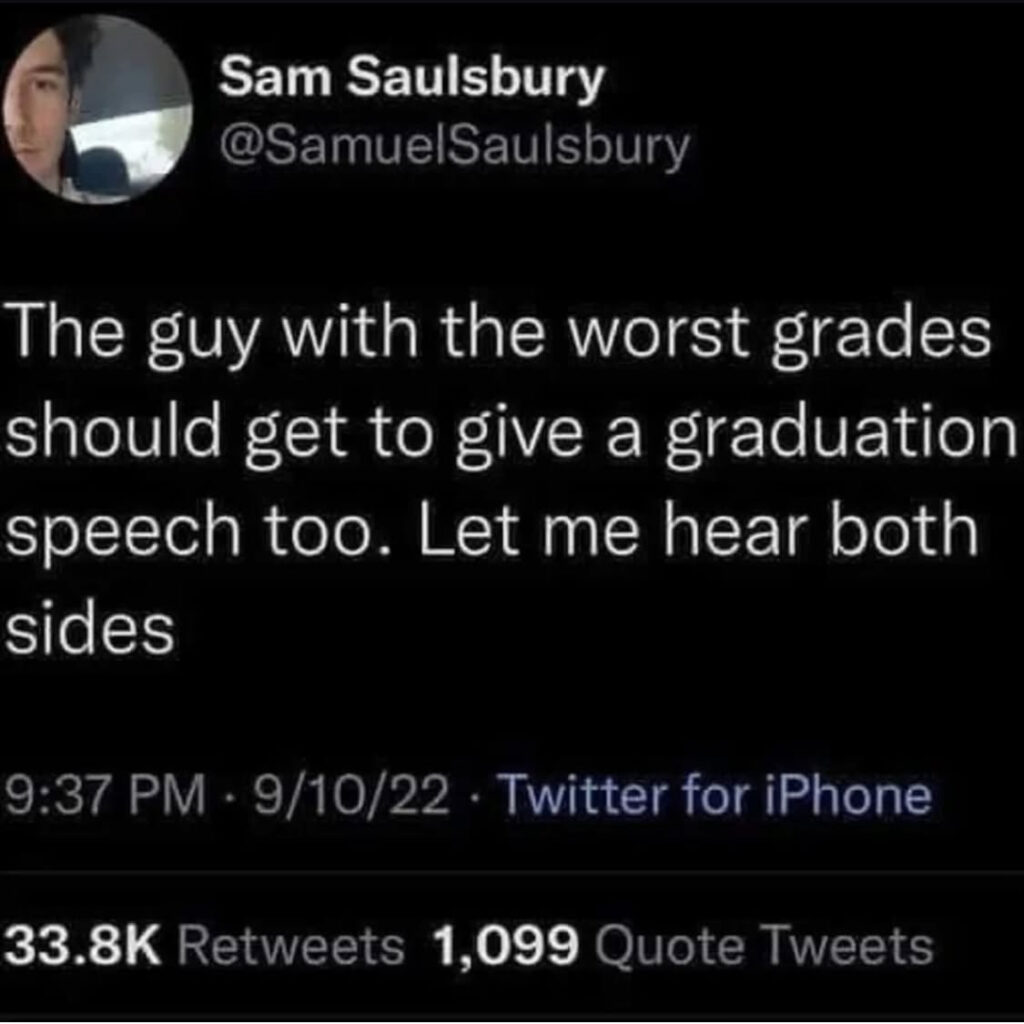

It is also essential to consider getting a wide range of perspectives from students. Although the meme below appears to be a joke, there is some accuracy to the sentiment.

It is easy to listen to those who say school works for them, but do we hear from those who hate the experience altogether?

How can educators better invite and respond to student concerns?

Many “student leadership” conferences are a mix of students who enjoy the school experience and are gifted academically (which doesn’t necessarily mean they are the smartest but are often the best at “school”), but does this validate the way things have always been done, or challenge our thinking on why school doesn’t work for many?

Deidre Roemer, superintendent of the School Distrist of South Milwaukee, and one of the most brilliant educational leaders I have had the opportunity to connect with over the years, had an incredible session with a group of her former district’s school leaders, and students who left the “traditional program” for alternative options that seemed to work better for them.

In the session, they shared why they left and what would have likely made them stay. It was a sobering session, and the administrators were incredibly reflective and thoughtful about what they would do as a result. That process should be happening more throughout all schools. Asking the question, “Why did you leave?” and “What would have made you stay?” is simple yet could have a profound impact on what we do moving forward. Again, not everything can be acted upon, but listening precedes action.

As a school administrator, I often said to my staff, “I cannot solve problems I do not know exist,” and in retrospect, I should have been more explicit in sharing that sentiment with the students.

What is the impact of grades on student curiosity and learning?

My reflection on this was inspired as I am reading through “Hopes for School” by recently graduated high school student Karen Phan and educator Jennifer Casa-Todd. Karen shares some powerful insights on her school experience, and how the experience seemed to shape her away from “curiosity” toward “compliance.”

In the book, here are a few of Karen’s quotes that stuck out to me:

“If I had the opportunity to do high school all over again, I would still choose grades over learning. But as I share in this chapter, I now realize how this was detrimental to my curiosity and growth.”

“I become an expert in the subject the night before an exam because I cram everything, but then I dump it all out of my brain once I hit Submit.”

“What my high school grades do a better job of measuring is how well I followed the directions on my assignments and regurgitated the lecture slides on an exam, and how much I exhausted myself.”

Again, this is one student’s perspective (although many are shared throughout the book with similar sentiments), so I ask: Is she wrong?

Karen’s perspective is something I have been discussing and wrote about in “The Innovator ‘s Mindset.” In the book, I shared the following:

I am not about absolutes, and my hope for this image is that it sparks more conversation than promoting “either-or” thinking. The way that I see the visual is as a spectrum to continue, and I hope that school promotes going further today than it has in the past.

For example, I think “consumption” is necessary to learning, but you make meaning and develop understanding through the “creation” of content. Watching a video can provide engaging content, but creating a video to share with others and the world on the same topic can promote a deeper understanding.

As I have shared previously, Adam Grant discusses the concept of teaching others to further your own learning in his book, “Hidden Potential,” and the ability to teach others promotes a deeper understanding of material beyond regurgitation:

“Psychologists call this the tutor effect. It’s even effective for novices: the best way to learn something is to teach it. You remember it better after you recall it—and you understand it better after you explain it. All it takes is embracing the discomfort of putting yourself in the instructor’s seat before you’ve reached mastery. Even just being told you’re going to teach something is enough to boost your learning.”

Adam Grant

Can educators improve learning within the constraints of standardized systems?

So, if the perspective of Karen and other students is that what many students become really good at in school is actually “school,” not necessarily learning, the next question is, “What can we do about it?”

Many adults will say that, as much as they agree with her, there is not much we can do. With standardized tests, system constraints, and other factors, we are limited in what we can change. In response to that sentiment, I share an answer I posted previously in this same post.

Kind of.

Of course, there are always forces that we must contend with that promote compliance over creativity and learning.

The way I have shifted my perspective on this is by focusing on the following: If we are focused on students achieving good grades, that doesn’t necessarily mean they are becoming good learners; however, if we focus on developing students as great learners, their grades will be fine.

Here is an example that I wrote about in “Innovate Inside the Box.”

Grades are a reality of the majority of schools and systems around the world. But “grades” have a finality to them, whereas “feedback” is essential to growth and learning, both in and out of school. The problem with grades is that they often encourage the practice of ignoring feedback. For example, I have had frustration over the years of providing thoughtful feedback in report card comments, only to have it ignored by looking at the number or letter that was mandatory to provide. I might as well have just written, “Have a great summer!” rather than going through the complexity of providing what I thought to be meaningful feedback.

What I wish I had done was a practice shared in “Innovate Inside the Box” by Kristy Louden, which involves the idea of “delaying the grade.” Here is what Kristy shared:

The solution was remarkably easy and accidentally originated out of my laziness (score one for being a little lazy!). Last year, kids had turned in essays on Google Classroom, but rather than pasting a completed rubric into their essay as I usually did, I made hard copies of the rubric and wrote on them.

This meant that I could return papers with comments but without grades.

And from this a whole new system was born: Return papers to students with only feedback.

Delay the delivery of the actual grade so student focus moves from the grade to the feedback. The simple act of delaying the grade meant that students had to think about their writing. They had to read their own writing—after a few weeks away from it—and digest my comments, which allowed them to better recognize what they did well or not so well.

The response from students was extremely positive; they understood the benefit of rereading their essays and paying attention to feedback. One boy said, “Mrs. Louden, you’re a genius. I’ve never read what a teacher writes on my essay before, and now I have to.”

Kristy had identified the “constraint of the system” and then found a way to promote learning within the process. (The entire book “Innovate Inside the Box” is focused on the realities of what many have to face in education, and how they can still promote deep learning.)

Moving Forward

As I shared earlier, we cannot act upon every suggestion or concern students have (and sometimes, there is a good reason why we wouldn’t), but when we know that sometimes the “process of school” can hurt learning long term for our students, we have to ask the question, “What do we have the power to do today to help students tomorrow?”

It is imperative to continue advocating for changes to the future of education, but that doesn’t necessarily benefit today’s students. Change what you can, and hopefully, the “innovative” practice you create to enhance learning opportunities for students within your current context will become the “best practice” of tomorrow.