In Part 1 of “Rethinking Grading and Assessment Practices,” I shared my thoughts on the question, “Why do we need to rethink how we assess and grade in schools today?”

In Part 2, I discussed how essential it is to lead this initiative with your community. If you try to do this “for” your community without their input, you might spend more time arguing than moving forward.

Today, I will focus on the question, “How could moving away from traditional grading to competency or standards-based assessments and a focus on giving feedback to improve deep learning and enhanced habits for growth and development?”

When I started this series, I had many conversations with educators. Based on their feedback, some of their strategies are fantastic, truly honoring the students and the learning process and opening doors that didn’t exist before. In some other conversations, there are still practices being used that were standard when I was a student. Some of those things might be good, and I have been really against the idea of using the word “traditional” in lieu of “bad.” Some new practices are terrible, and some old ones are great. The time they were developed is less consequential than how effective they are today.

That said, I am just sharing some of my insights and hopefully adding and/or starting a conversation.

Let’s start with an analogy before we get into any big idea strategies.

Who would you want flying your plane?

I am going to give you two people to consider in this scenario; a pilot that knows 100% of what it takes to fly a plane and has the ability to do so but is always late or a pilot who knows about 50% of what it takes, but has a great attitude and work ethic! Heck, let’s even give that second person a 75% knowledge base. Who would you pick?

If your answer is like mine, it would be neither.

The first pilot will probably get me to where I need to be, but I, and many others, will be late for our destination. That doesn’t fly with me (see what I did there?)

The second pilot might crash us, but they might be all smiles while doing it.

Neither seems to be a good option.

But if I had to pick, it would be the first.

I would rather be late than dead, but I may be just old-fashioned that way.

But in each scenario, the pilot’s knowledge, ability, and attitude matter when we consider who is flying the plane we are boarding.

Knowledge, Attitude, and Work Ethic Are All Important

But it doesn’t mean they should all be lumped together in one grade.

In each of the scenarios above, I laid out what was good, bad, and what probably should be fixed.

If we could get that first pilot to show up on time, then that would be helpful. That second pilot has a terrific demeanor, but they aren’t ready to take on the responsibility of flying themselves and others if they don’t understand fully what it takes to fly a plane.

If you lumped the grades together, though, based on a combination of knowledge, ability, attitude, and work ethic, they could get relatively the same mark, but you would be much less safe in one scenario than the other. You might not know that until you get in the air.

I was lucky enough to be a part of Parkland School Division years ago that understood this insight, and they had two different reporting tools. One specifically for a student’s knowledge and understanding of what they knew and understood based on the curriculum, and another assessment tool based on the work ethic and personal and social responsibility. Too often, the conversation is whether we should combine the two tools or eliminate one totally. I believe both are important and should be separated accordingly.

Yes, this student understands everything they need to do in math, but they also have a terrible work ethic that might catch up with them later when the subject area might become more complex. But then the discussion could be that their work ethic is terrible in class because they are bored with the content that isn’t challenging.

Whatever it is, a student shouldn’t lose credit or grades for content they fully know. But I also think it is essential to look at other factors beyond knowledge and be able to discuss that as well.

Because maybe it’s you (or me)?

Early on in my career, before Parkland, combining things like attitude, homework completion, and knowledge was commonplace in the schools I worked and in my practice.

I remember one student, specifically in my grade nine math class, who was brilliant but also had a terrible attitude and was often mouthy toward me. It bothered me, and I would use the “attitude” marks as a carrot and stick to curb the behavior.

During Parent-Teacher Interviews that year, her mom came and talked to me and wondered why her child only had a 93% in my class overall (which I thought was a grade that no one would complain about!) since she never received a mark lower than that on any exam or project we had done.

I said, “She is quite brilliant, but honestly, her attitude is terrible, and that’s where she lost marks.”

The mom responded, “Only for you.”

I asked my colleagues if they had ever had an issue with this student, and all of them, like ALL of them, said she was fantastic, and they had zero problems.

She had lost grades because we had a personality conflict. Instead of addressing this and trying to figure out a solution, I just figured she cared about grades, and I would correct her behavior through the attitude mark.

#BadTeachingMoment

I am so glad that the parent shared that insight with me because not only did it remedy the relationship in the classroom, it made me rethink how I was grading a student and how I was using marks and averages as a behavior correctional tool more than anything.

Eventually, I stopped using “marks” entirely.

I have watched some schools move away from percentage grading, or A-F scales, and then use 1-4 scales, which in the mind of a parent or student is just a different type of A-F scale. They convert the 1 to an A: same thing, different package.

We moved away from grading to a more standards-based assessment practice (some call it competency-based or something else, but hopefully, you get what I mean). Instead of giving a “grade” or a number on an assignment, we would say what a student could and couldn’t do. Going back to the pilot analogy, it is essential for the pilot that would score a 75% to move from, here are the things that you can do, and here are the areas you need to grow. I would rather a pilot not know how to turn on the air conditioning than not know to land. One element is more imperative than the other.

In my graduate class with UPenn, I go over the assessment practices at the beginning of the class and share that there are no grades for the class. Still, I am focused on them having a deep understanding of the content and the ability to apply it to their current work. There are no penalties for “late” assignments because I do not have rigid timelines for completion, but I provide a suggested schedule to manage their time. Some students in the class complete things right on that recommended time, and others don’t. But all of them deeply understand the content, even if they need more direction. When I go through their assignments, I share what stuck out to me and what I appreciated and then ask some further leading questions to clarify their understanding if needed.

I understand this is with adults and is much different than students. But the one thing that I ask them about the process in the class is that if they find how I assess their learning and how feedback is provided, they consider how they implement the strategy in their schools and districts. What I am trying to get students to do in the class is to focus on the learning and how they utilize it in their context rather than focusing on a “grade” to be obtained. I can honestly say that in the entire time I have taught this class, only once did a student not complete the course that showed proof of their learning, but I also know that they had other life events that interfered with the class. They were offered to complete it at a different time, and the opportunity was available.

This was very similar to how I assessed later in my teaching career. I tried to get students to focus on learning rather than grades. My belief is that if I get students to be really good at taking tests, they might not end up being good learners. But if I develop them as great learners, they will be fine on the test.

I know this is simple thinking and much more complex in the doing part, but we have to ask what we are trying to accomplish in our work.

So let’s go back to the overriding goal:

Again, not always easy. But here is something to consider when we are struggling with the complexities of moving away from grading practices as we know them:

What are the barriers we face, and what solutions, in our own context, can help us move forward?

But people are still expecting grades to get into college and post-secondary!

True.

And at some point, some schools and teachers will have to assign a grade to students, even when we know that having learners focus on feedback is much more effective for continued learning than providing a grade.

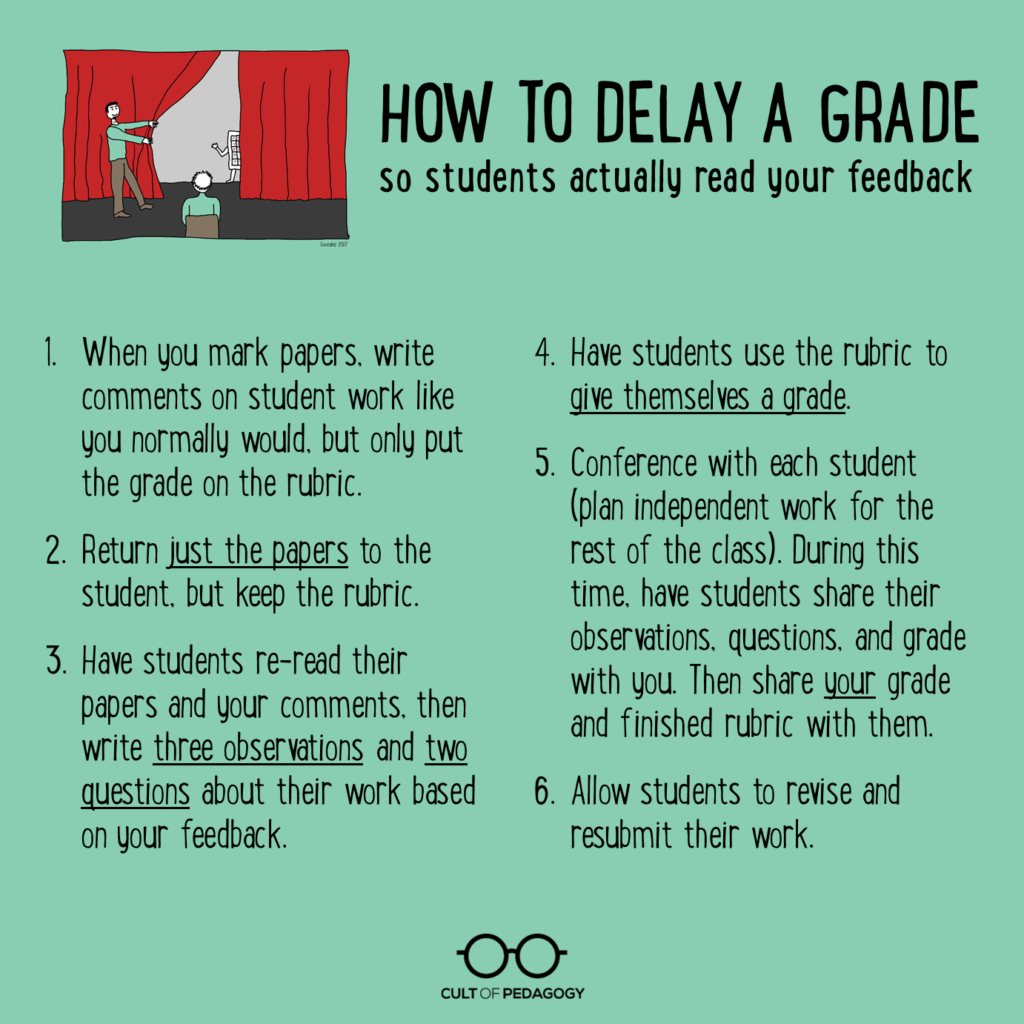

That is why I really appreciated this article from Kristy Louden on “Delaying the Grade,” written in 2017. In it, Kristy shares the frustration of having to provide a grade and a possible “fix” for the process:

You should read the whole post, as it provides some great strategies for the process.

But can a student still end up getting a zero in class?

All of what I am sharing in these posts are based on my own views and are things I have progressed on, but people might not like my answer to the question, “Can a student get a zero on an assignment?”

My answer unequivocally is “yes.”

But not because they didn’t hand it in or had a bad attitude.

A zero seems appropriate if a student knows “zero” percent of the content.

Again, the pilot analogy.

I know zero percent of what it takes to fly a plane. Would you bump my grade to 50% to ensure that I can still pass flight school? If so, would you want to fly on my plane at the end of class?

But we have to identify that sometimes a student receives a zero in a class not because they know 0% of the content but because of handing in a late assignment and getting punished for work ethic, and it is reflected in how they are graded on their content knowledge even though it is not accurate. That doesn’t benefit the student, family, or the next teacher.

Or, sometimes, the assessment tool isn’t just grading their content knowledge but something else hidden in the process.

For example, many schools are focused on providing “common assessments” and ensuring that students have assessment tools (this was quoted to me by an administrator) in the “same style, place, and time.”

For example, sometimes, when we ask a student to share their understanding of a science concept through a test or written explanation, we are not only assessing their understanding of science but their ability to write their understanding of the concept. In fact, for some, that might not lead them to be assessed on their science comprehension at all.

Are we giving students the opportunity to share their learning and understanding in ways conducive for them to share, or are we basing learning on what is easiest to be “graded” and captured by the adults?

Moving Forward

There is so much more I could write on this topic than what I did today, but I wanted to stop here and have the last paragraph lead to the final part of the series. There are many opportunities for students to share their learning in meaningful ways while helping them find their own pathway to success, and we need to embrace those opportunities.

In the next and final part of the series, I am going to dig into how portfolios could truly help our students share their learning in a way that ensures we are still doing our job while pushing their knowledge now and providing them something that could be more beneficial than a traditional report card for the next phase of their lives.

Questions for Consideration

1. How can we separate content knowledge from attitude and work ethic in our current reality to report on both while accurately assessing a student’s understanding of learning?

2. What is our current reality with “grading,” and how can we help students focus more on feedback than numbers and scores?

3. What are the benefits and detriments of common assessments? Is there a better way to help students share their learning?