I saw this TikTok video from Brian Fretwell on the idea of “accountability,” I am not sure the message pushes the concept of accountability, but it is an excellent message nonetheless.

@brian_fretwell This is the accountability we teach #story #parents #reportcard

I struggle with the idea that this is about “accountability” because it is about the adults in the situation helping students focus on their strengths and use those things to help build their weaknesses.

Is the video about child accountability or good adulting?

Brian’s advice was to help focus people (the child in this case) on what they are good at and learn from their strengths.

It is great to talk about this with adults to kids, but what about adults with adults?

I wrote about this very idea in “The Innovator’s Mindset,” and if you have not read the book yet (you can get your copy here!), this is what I wrote in 2015:

Teachers often design classroom experiences that mimic the school culture and the learning opportunities they’ve experienced. So when teachers are part of a culture that is built on a deficit model, that mentality often manifests itself in the classroom. One example of this is the way testing data is used to identify and address areas of weakness. This practice leaves a lot of educators feeling demoralized in their work.

Recently, I read an article in the Toronto Sun titled “Literacy Rates up but Students still Struggling with Math.” The piece about Canada’s Ontario province focused entirely on math. Not one sentence celebrated the province’s improvement in literacy. The focus was, instead, on how math instruction and learning were not up to par. Should Ontario just ignore math scores and adopt the “you win some, you lose some” mentality? Absolutely not. Neither should its complete focus be on improving declining math results. Yet we continue to play this game of educational “whack-a-mole,” where one problem pops up and we focus on that until the next issue arises.

We cannot forgo a focus on our strengths for the sake of only emphasizing the areas where we struggle. But that’s what happens time and again. The deficit model compels administrators and educators to overcompensate in the areas that need to be “fixed.” When that occurs, all the great things that are already happening are quickly forgotten. The bottom line is: an environment where the message is always “we are not good enough” can be demoralizing and counterproductive for all stakeholders.

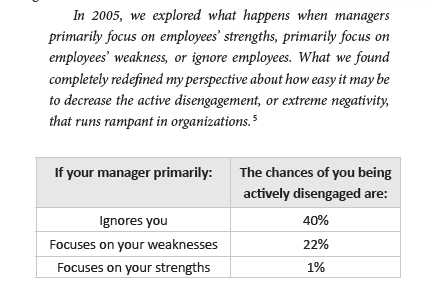

Tom Rath, the author of “Strengthsfinder 2.0,” also shared that a “strengths-based approach” in organizations can improve adult engagement in the workplace.

I am all for building on the strengths of the child. Not only does it help develop passions and interests, but it can also help them in areas of growth. Confidence and competence are often interconnected.

But it starts with doing the same for the adults. Start with the areas of strength and what is going right (in an authentic way), and the other areas will grow.

If we want that for our students, we should want it for the adults that work with them every day.